Some agricultural practices as a complement for primate conservation in human-modified Neotropical landscapes

�

Alejandro Estrada

1

1

Estaci�n de Biolog�a Tropical Los Tuxtlas, Instituto de Biolog�a, Universidad Nacional Aut�noma de M�xico. Email: [email protected]

�

Abstract

While there is a general perception that agricultural activities are the principal threat to primate biodiversity in the tropics, in this paper I address this issue and argue that in fragmented heterogeneous Neotropical landscapes some agricultural practices may favor primate population persistence in human-modified landscapes. To explore these issues I examined pressures upon forested land derived from human population growth and levels of poverty for the Mesoamerican and Amazon basin regions, and present relevant results of recent surveys of presence and activities of primate populations in agroecosystems in several landscapes in

Mesoamerica

. I further assess the possible benefits of presence and activities of primates to agroecosystems, and stress the value for primate conservation of some agricultural practices in the Neotropics

.

�

Key words:

Neotropical primates, agroecosystems, conservation

�

Introduction

Pressures for land use have been pointed out as the major cause of tropical rain forest loss and fragmentation throughout the world (Donald 2004), and a major cause of increases in rates of species extinction in recent decades (Laurance et al. 2002). Fragmentation of habitat and stochastic forces along with the increase rarity of habitat play an important role in further declines of animal populations and species at the local level (Heltne et al. 2004a and references there in). Growing empirical evidence however suggests that not all species decline toward extinction following fragmentation (Henle et al. 2004b), and that, in some cases, species resilience may be higher than expected (Estrada et al. 2006a). Similarly, the focus of landscape studies in the tropics has been the "habitat" and not the "matrix" (the non habitat surrounding the native habitat patches of interest), but recently attention has been called to the value of matrix habitats for preserving large segments of biodiversity (Ricketts 2001; Lugo 2002; Murphy and Lovett-Doust 2004). This binary perspective has been applied to the study of the consequences of habitat fragmentation on animal communities in the Neotropics, mainly based on a large body of research conducted in

South America

and where the majority of the studies have examined the biological richness of forest fragments and how such richness is affected by isolation, edge effects, invasive species, and temporal isolation and management (Laurance et al. 2002).

�

Agroecosystems, covering more than one quarter of the global land area, reaching about 5 billion hectares (Altieri 2003; Vandermeer 2003), are ecosystems in which people have deliberately selected crop plants and livestock animals to replace the natural flora and fauna.

� There are highly simplified agroecosystems (e.g. pasturelands, intensive cereal cropping, monocultures), but there are also agroecosystems that support high biodiversity in the form of polycultures and/or agroforestry patterns (Moguel and Toledo 1999).

� However, diversity in many cases is maintained not only within a cultivated area.� For example, many farmers maintain natural vegetation adjacent to their fields, and thus obtain a significant portion of their subsistence requirements through gathering, fishing, and hunting in habitats that surround their agricultural plots (Altieri 2003). Depending on the level of biodiversity of closely adjacent ecosystems, farmers accrue a variety of benefits and ecological services, harvesting for example native and naturalized vascular plants for dietary, medicinal, household, and fuel needs, organic fertilizers, fuels and religious items, etc. and general ecological services from natural vegetation growing near their properties. (Altieri 2003; Vandermeer 2003

�

In this paper I explore these issues, examine pressures upon forested land derived from human population growth and levels of poverty for the Mesoamerican and Amazon basin regions, and present relevant results of recent surveys of presence and activities of primate populations in some agroecosystems. I further assess the possible ecological services primates may provide to these land uses and stress the value for primate conservation of some agricultural practices in the Neotropics

.

�

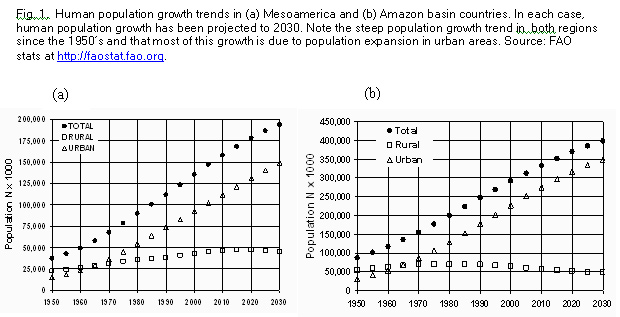

Human population growth, poverty and deforestation trends

�

Current human population in

Mesoamerica (8 countries) is estimated to be about 48 million people, with a growth rate of 3% since 1950's, it is expected that the population will double in 20�35 years (

http://faostat.fao.org/; http://earthtrends.wri.org/). Average human population density in this region is 82.8 + 92.1 people/km

2 (world average 41.5 people/km2), but it varies across countries with El Salvador

having the highest population density (29 people/km2) followed by Guatemala

(119 people/km2) and Costa Rica (74 people/km

2). In the rest of the countries, except Belize

where population density is the lowest (11 people/km2), population density varies from 31 people/km2� (

Mexico south) to 57 people/km2 (Honduras

) (Table 1). In Amazon basin countries (N = 9) human population approaches 300 million people and growing at a rate of 2.6% per year. Average population density for these countries is estimated at

20.2 + 15.0 people/km2. Highest population density is found in Ecuador

(46 people/km2), Colombia (38 people/km2

) and Venezuela (28 people/km2), followed by

Peru (21 people/km2),

Brazil (20 people/km2) and Paraguay

(14 people/km2). Lowest population densities are found in Bolivia

(8 people/km2), Guyana (4 people/km2

) and Surinam (3 people/km2) (Table 1)